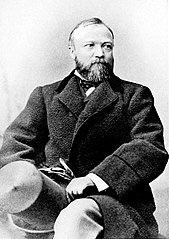

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was a 19th century Scottish immigrant and steel industry tycoon. Considering the wealthiest Americans in history, Forbes ranks Carnegie #5, having had wealth valued at 0.60% of the entire U.S. economy. After selling his company to U.S. Steel in 1901 at the age of 65, he focused on a life of philanthropy. In addition to multiple donations, perhaps his most well-known enterprise at that stage entailed donations of about $60 million to fund over 1,000 libraries in the United States. (See bio)

This behavior reflected a personal belief of his regarding the responsibility of those with great wealth to enrich the lives of others in a lasting way. In June of 1889, he published the article Wealth in the North American Review. The article begins:

The problem of our age is the proper administration of wealth, so that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship. The conditions of human life have not only been changed, but revolutionized, within the past few hundred years. In former days there was little difference between the dwelling, dress, food, and environment of the chief and those of his retainers. (p. 653)Carnegie goes on to describe how the relatively wealthy in the past still lived in modest accommodations relative to the poor. But the industrial age revolutionized the disparity in wealth. He thus believed in a certain obligation of the rich for the poor "so that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor."

On November 24, 2013, Pope Francis I released the apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, also known as The Joy of the Gospel. Although an apostolic exhortation bears less authority than, say, a papal encyclical, and although this exhortation does not define faith or morals, it still calls for the reverential consideration proper to the papal office.

Pope Francis, like Carnegie, speaks of the phenomenon of a disparity in wealth between the wealthiest and the poorest:

While the earnings of a minority [i.e. the wealthy] are growing exponentially, so too is the gap separating the majority from the prosperity enjoyed by those happy few. (#54)Both men indicate this income gap is remedied when the wealthy grant certain ethical considerations proper to Christian philosophy. Says Carnegie:

The highest life is probably to be reached...while animated by Christ's spirit, by recognizing the changed conditions of this age, and adopting modes of expressing this spirit suitable to the changed conditions under which we live; still laboring for the good of our fellows, which was the essence of his life and teaching, but laboring in a different manner. This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of Wealth: First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and after doing so to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community... (661-662)You see Carnegie here promoting the Christian virtue of modesty as well as the idea of the wealthy's call to utilize "surplus revenues" for the betterment of society. This sentiment finds itself presented anew in Pope Francis' exhortation:

In this system, which tends to devour everything which stands in the way of increased profits, whatever is fragile, like the environment, is defenseless before the interests of a deified market, which become the only rule. ... Behind this attitude lurks a rejection of ethics and a rejection of God. ... Ethics––a non-ideological ethics––would make it possible to bring about balance and a more humane social order. With this in mind, I encourage financial experts and political leaders to ponder the words of one of the sages of antiquity: “Not to share one’s wealth with the poor is to steal from them and to take away their livelihood. It is not our own goods which we hold, but theirs”. ... Money must serve, not rule! The Pope loves everyone, rich and poor alike, but he is obliged in the name of Christ to remind all that the rich must help, respect and promote the poor. I exhort you to generous solidarity and to the return of economics and finance to an ethical approach which favours human beings. (#56-58)Carnegie also considers the difference between donation in the form of welfare to individuals and what I would describe as systemic donations that enable the many. In the below quote, he ponders the hypothetical donation of Mr. Tilden:

But let us assume that Mr. Tilden's millions finally become the means of giving to this city a noble public library, where the treasures of the world contained in books will be open to all forever, without money and without price. Considering the good of that part of the race which congregates in and around Manhattan Island, would its permanent benefit have been better promoted had these millions been allowed to circulate in small sums through the hands of the masses? Even the most strenuous advocate of Communism must entertain a doubt upon this subject. Most of those who think will probably entertain no doubt whatever.This mentality does not seek to give where use of the contribution will quickly pass. It resembles the adage: "Give a man a fish, and he eats for a day. Teach a man to fish, and he eats for a lifetime." Pope Francis describes a similar temperament with regard to welfare and systemic giving:

Welfare projects...should be considered merely temporary responses. ... Growth in justice requires more than economic growth, while presupposing such growth: it requires decisions, programmes, mechanisms and processes specifically geared to a better distribution of income, the creation of sources of employment and an integral promotion of the poor which goes beyond a simple welfare mentality. (#202, 204)Both Carnegie and Francis assert a certain weakness in making small donations which result in "temporary" and non-"permanent" benefits. In other words, they believe the systemic problem will persist under such giving. Regarding Carnegie's mention of Communism, in TCV's previous post, I also cited the Pope acknowledging the Church's opposition to Communism.

Implicit in Carnegie's discourse is the notion that human beings have in themselves a dignity worthy of the assistance of others. His call to the wealthy to make use of their surplus wealth for the betterment of society reveals this. Although this parallel is less explicit than the others, I want to examine Pope Francis' reflection on the human aspect:

The current financial crisis can make us overlook the fact that it originated in a profound human crisis: the denial of the primacy of the human person! We have created new idols. The worship of the ancient golden calf (cf. Ex 32:1-35) has returned in a new and ruthless guise in the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose. The worldwide crisis affecting finance and the economy lays bare their imbalances and, above all, their lack of real concern for human beings; man is reduced to one of his needs alone: consumption. (#55)Keeping with the Pope for another moment, I think he carried this idea forward to a vital moral issue of our time––the matter of abortion. Later in the encyclical, while describing various groups in society sometimes viewed as instruments of profit to others, the Pope tied in the matter of the unborn:

Among the vulnerable for whom the Church wishes to care with particular love and concern are unborn children, the most defenceless and innocent among us. ... Human beings are ends in themselves and never a means of resolving other problems. Once this conviction disappears, so do solid and lasting foundations for the defence of human rights, which would always be subject to the passing whims of the powers that be. ... Precisely because this involves the internal consistency of our message about the value of the human person, the Church cannot be expected to change her position on this question. I want to be completely honest in this regard. This is not something subject to alleged reforms or “modernizations”. It is not “progressive” to try to resolve problems by eliminating a human life. On the other hand, it is also true that we have done little to adequately accompany women in very difficult situations, where abortion appears as a quick solution to their profound anguish, especially when the life developing within them is the result of rape or a situation of extreme poverty. Who can remain unmoved before such painful situations?

Pope Francis, at St. Peter's Square, Nov. 13, 2013

Strains of the same mentality which denies or forsakes human dignity can permeate both the most virulent profit-seeker, such as a human-trafficker, and the most sympathetic victim, a woman impregnated by rape whose choice for life communicates profound heroism. The Pope is exhorting souls to reject the idea that humans are commodities to be used or eliminated to solve a problem as if they were tools. I have seen online proponents of abortion defend it on the grounds that the child would cause financial hardship. In the examples in this paragraph, the human-trafficker certainly merits less sympathy than the young woman who reluctantly finds herself pregnant and seeks abortion, however, in both cases, the idea that human life is secondary to financial advantage exists in one form or other.

This article is not intended to claim that the totality of Carnegie's and Pope Francis' arguments are identical from top to bottom, nor is it intended to be viewed as an endorsement of every word in the respective documents. Rather, it is to focus on several characteristics in which Carnegie and Francis have overlap. I think part of the intrigue in this comparison is that one man is among the wealthiest in world history and the other is perhaps the most well-known contemporary religious leader in the world, known for carrying his own luggage and personally calling common citizens, including a rape victim. One could not automatically reject Pope Francis for being an economic outsider, ignorant about economics, at least not entirely ignorant, when several of his arguments reflect the sentiments of one of the most successful entrepreneurs in history.

Both men acknowledge an economic disparity among society. Neither speaks to eliminate the wealthy, but of the wealthy's call to assist others. Neither seeks to solve the disparity with mere welfare distribution. One could say these men are both opposed to free market "greed" while yet rejecting a Communist solution––which, as another Pope, Pius XII, described in Divini Redemptoris, culminates "in a humanity without God." Both men recognize due regard members of society are called to have for each other. And both include Christ in the remedy.

Carnegie photo at top is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Yet Carnegie had a reputation for underpaying his workers and caring more about profit than workplace safety. Is that the cost of philanthropy?

ReplyDelete